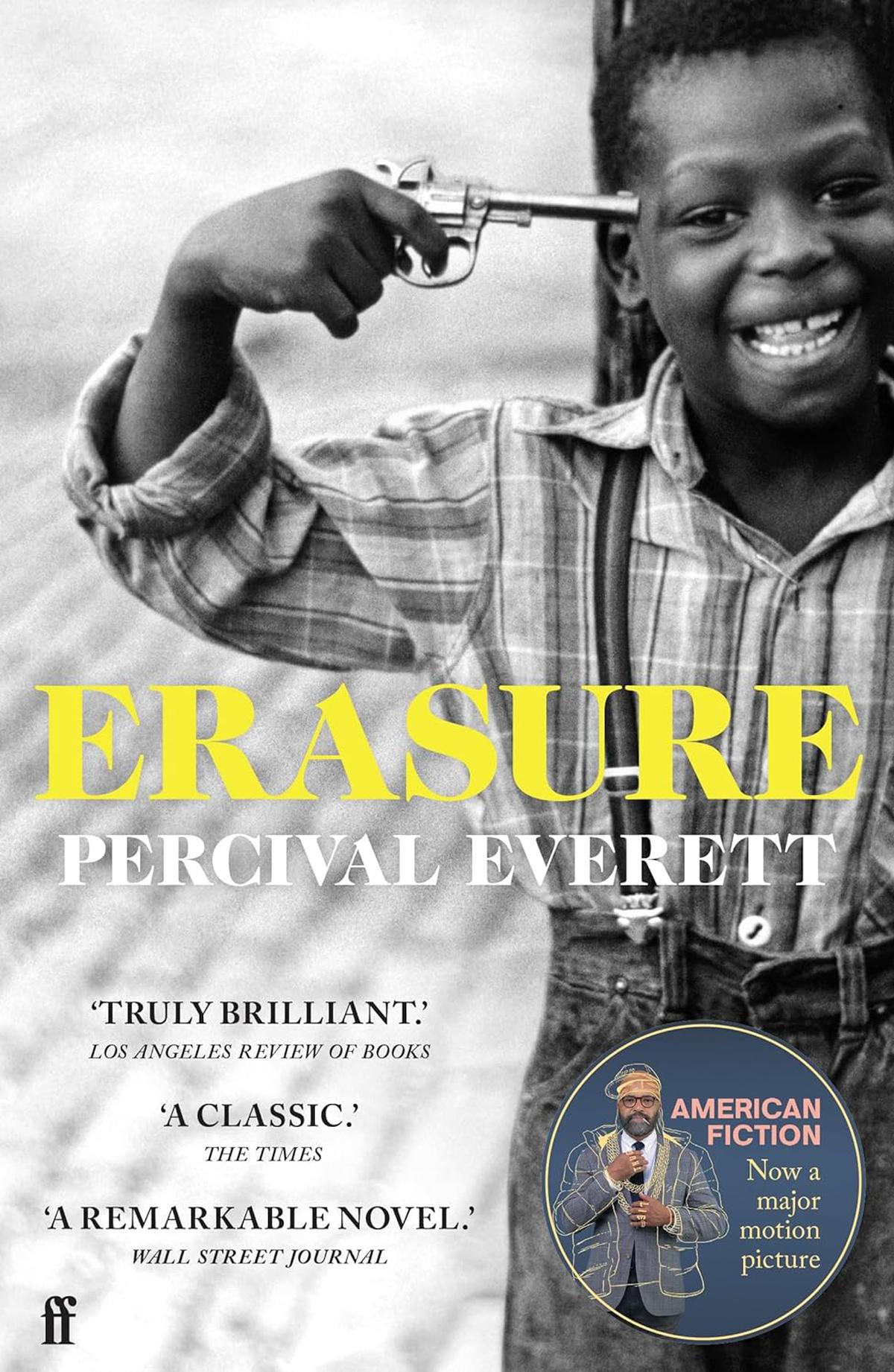

Looking back at Percival Everett’s ‘Erasure’, the novel behind the Oscar-winning movie ‘American Fiction’

[ad_1]

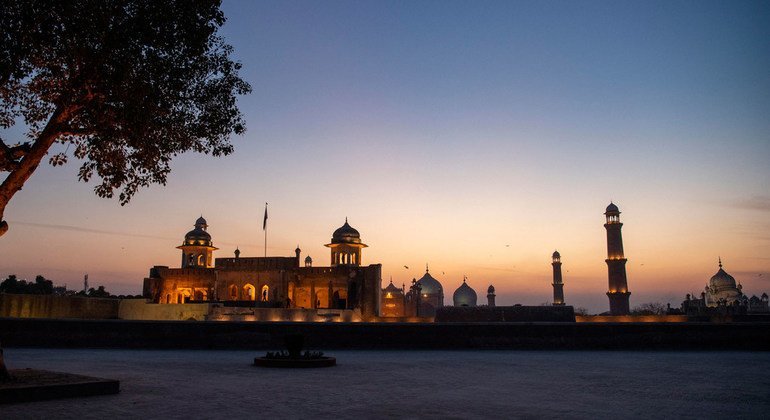

A still from ‘American Fiction’, which won the Oscar for best adapted screenplay this year.

The literary world is abuzz with excitement about the new novel by American writer Percival Everett. James, a revisiting of Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, is told through the perspective of Jim, Huck’s companion slave. Finding Jim absent for long stretches in Twain’s tale, Everett wanted to give him an opportunity to be present in the story.

Everett is also in the spotlight for his 2001 novel, Erasure, which was brought to life on screen by journalist-writer Cord Jefferson, as American Fiction. The feature film won the Oscar for best adapted screenplay this year.

At one level, Erasure is about a writer who can’t fit in; Thelonious ‘Monk’ Ellison — right away there are hat-tips to a path-breaking musician and a writer — is upset with how his published works are treated. They don’t sell well and he is having trouble getting published in the first place because what he wants to write is not “black enough”. His publisher urges him to try something like his The Second Failure, a ‘realistic’ novel that did rather well.

Monk cringes at the thought because he hated writing that novel about a young black man who cannot understand why his white-looking mother is ostracised by the black community; he hated reading the novel and hated to think about it.

Being black

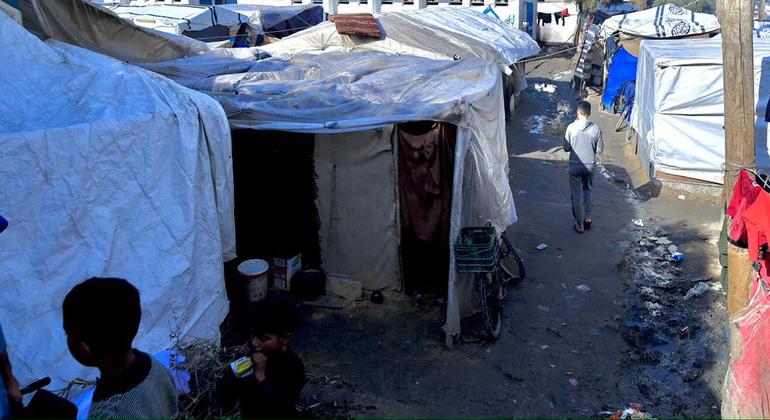

But then, a fellow black writer, Juanita Mae Jenkins, is earning all the praise and the moolah — and space at the bookstore — for her novel We’s Lives in Da Ghetto, and Monk on a whim decides to write a novel on “which I knew I could never put my name”. Thus is born My Pafology, later called F***, by Stagg R. Leigh, which has all the tropes perceived to be black.

It’s the story of Van Go Jenkins, who in his 20s has already fathered four children by four different women and is trying hard to keep a job against all the odds stacked up against him. At one point, he is working for a certain Mr. Dalton, black and rich who lives in a mansion far away from the usual black neighbourhoods. “‘It is a mansion, Mama,’ I say. ‘That nigger is loaded.’ ‘Don’t be calling Mr. Dalton that,’ she say. ‘You call me that,’ I say. ‘Cause he gots bucks he ain’t no nigger? Cause I ain’t got nuffin, I am?’” Needless to say, this novel sells for $600,000 and Monk feels a “great deal of hostility toward an industry so eager to seek out and sell such demeaning and soul-destroying drivel”.

But this is an Everett novel; race, identity, inequities, history, politics are important; equally, it works on several other layers, and these nuances and its spirit, the language, touches of humour, irony and absurdity, have been wonderfully caught by Jefferson for the screen.

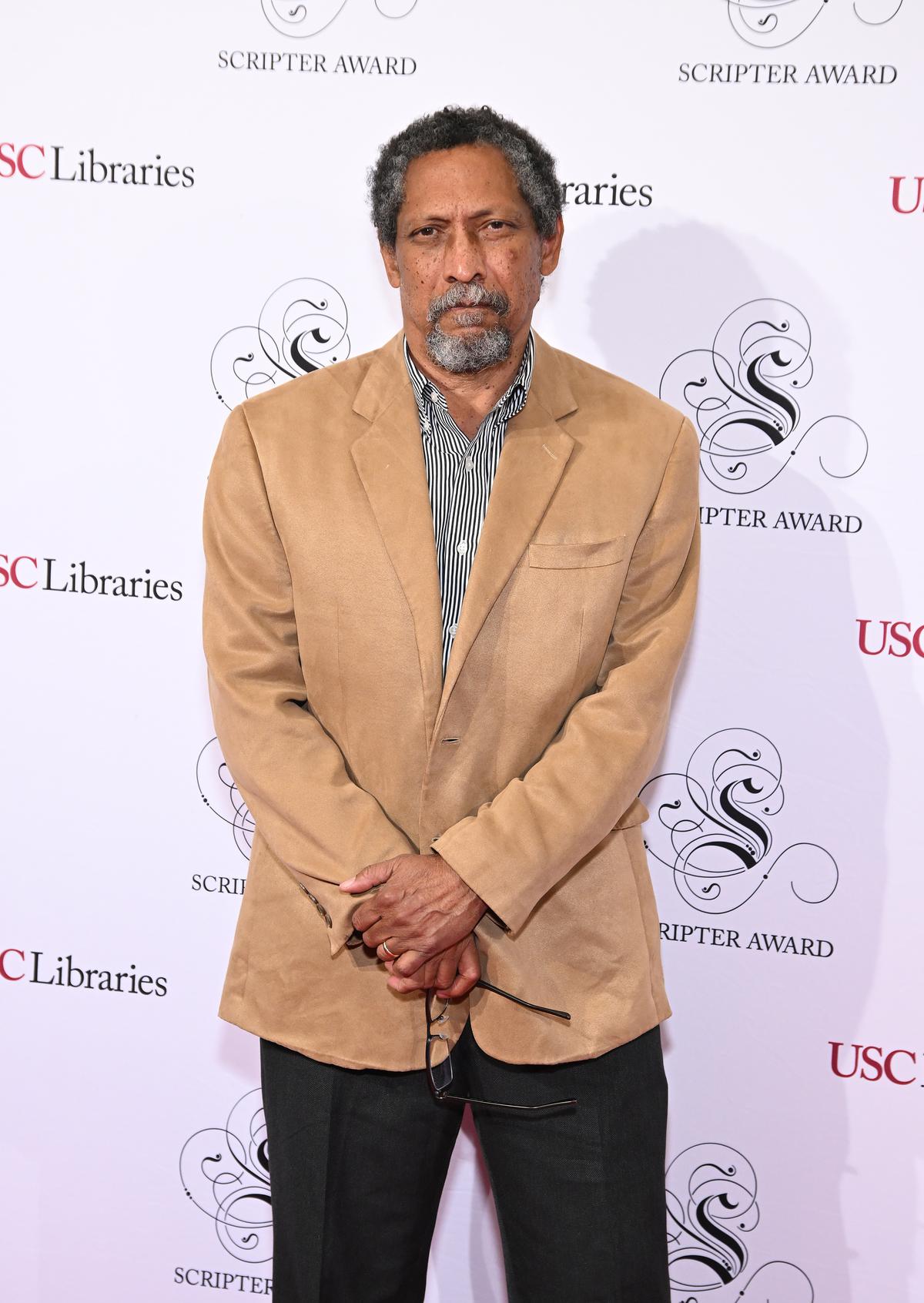

Author Percival Everett

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

Monk hails from a family that is reasonably well off, with two homes — his father, who has passed on, was a doctor (like Everett’s too), his mother is losing her mind, and his siblings are doctors. The conversations they have open readers up to a black world they are not used to reading about. The novel looks forward to the breakdown of abortion rights in America — the overturning of Roe v. Wade finally happened in 2022. In a chilling turn of events, Monk’s sister, Lisa, is gunned down for her work at an abortion clinic by a pro-life protester; the film tells it differently, but her end is sudden and no less difficult.

In interviews, Everett has said that Erasure “is about the impediments to making art that our culture puts in front of us”. And that’s what the 67-year-old, who teaches English at the University of South California, has pushed against in all his hard-to-categorise work. He has been a Pulitzer Prize finalist in 2020 with Telephone, which has three versions, and was shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 2022 for the satire, The Trees, about a murder mystery with roots to a lynching from the past, but told with crackling humour, if that is possible for such a dark moment of American history. In an interview to bookerprizes.com, Everett said: “If one can get someone laughing, then one can use that relaxed state to present other things.”

In that same interview, he explains why he thinks reading is one of the most subversive acts: “No one can control what minds do when reading: it is entirely private. We make of literature what we need to make. This is true of art.”

Everett lives by this dictum in his writing — James is his 24th novel, and he has written short stories, poems and a children’s book as well. He will not describe himself or his work, readers have to make of them what they need to make.

The writer looks back at one classic every month.

[ad_2]