Finding screen space for Dalit-Bahujan cinema

[ad_1]

‘Popular cinema hardly represents the aspirations and values of the Dalit-Bahujan social groups’

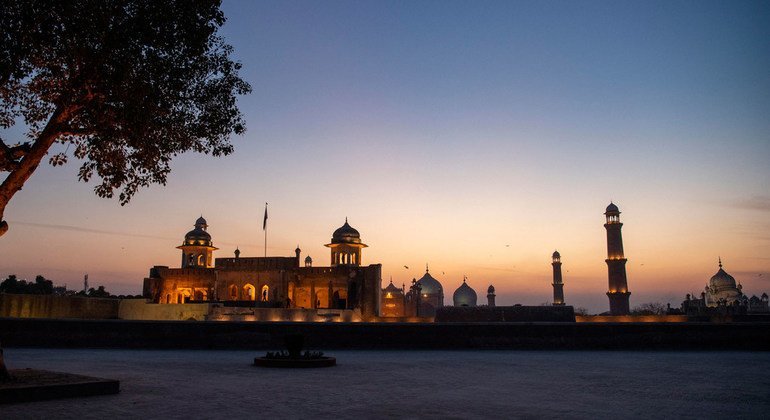

| Photo Credit: Getty Images/iStockphoto

In 2022, the box-office debacle of big-budget populist Hindi films (Cirkus, Laal Singh Chaddha, Dhaakad and Samrat Prithviraj) offers a clue that cinemagoers are rejecting the ‘masala-clad’ mindless cinema and are looking for newness and artistic calibre. Though there were other releases such as Gangubai Kathiawadi, Jhund, Anek and Salaam Venky that have engaged with serious issues of marginalised communities, sadly, these films have not emerged as a popular genre, making it a new alternative in Bollywood cinema. Cinemagoers still find meaning mainly in the conventional slapstick entertainment and often ignore the socially relevant films.

A ‘meaningful’ genre

The recent arrival of a small but impressive genre of Dalit-Bahujan cinema is a welcome attempt to change the taste of cinema goers. This cinematic mode wishes to entertain the audience with creative narratives, clubbed with the values of realism and social responsibility. However, it is too early to suggest that this ‘responsible and meaningful’ genre will bring in radical change. Therefore, a conscious and intelligent audience, especially Dalit-Bahujan viewers, has to promote this new initiative for more nuance to cinematic narratives.

There are almost no studies about the demography of the Hindi cinema audience. It is well known that Hindi mainstream cinema as well as experimental or art-house cinema often cater to the cultural taste and social interest of the middle-class social elites. Popular cinema hardly represents the aspirations and values of the Dalit-Bahujan social groups. In the post-liberalisation phase, especially with the arrival of multiplex theatres, the middle class and elite audience may have emerged as the main patrons of films and theatres, relegating the Dalit-Bahujan audience to the sidelines.

If one looks at the advent of cinema in India, one finds that artists and technicians from Maharashtra, Punjab had an influential role in the Hindi film industry. In the post-Partition period, artists (particularly from the erstwhile Punjab province) moved to Bombay, subtly dominating the film business. Popular actors and directors (Prithviraj Kapoor, Dileep Kumar, Raj Khosla, Vijay Anand, and Dharmendra) became the leading figures who defined the foundational norms of Hindi cinema. Their cinema celebrated the values of secular nationalism and socialism and narrated stories that resonated with the poor classes. Importantly, the dynamic presence of Parsi and Muslim film-makers such as Firozshah Mistry, Ardeshir Irani, Sohrab Modi, Khwaja Ahmad Abbas, Mehboob Khan, etc. established the ‘Muslim social’ genre as the integral part of Hindi cinema.

The rich contributions by the Punjabi, Parsi and Muslim film-makers have led to the creation of a secular audience for cinema — their stories revolved around the social and cultural issues of the Muslims (Pakeezah), the poor migrant working class (Awaara) and women (Bandini), making cinema a responsible art form for social change. However, the caste and Dalit question often remained peripheral during the ‘golden age’.

In the mid-1970s, art-house cinema further enriched Hindi cinema with its nuanced depiction of urban poverty (Chakra), issues of migrant labour (Disha), unemployment (Salim Langde Pe Mat Ro) and patriarchy (Nishant). The social questions of feudal exploitation (Manthan), caste violence (Damul) and Dalit repression (Giddh) too gathered momentum in this phase. Unfortunately, the parallel cinema movement failed to create an audience that could make meaningful cinema more popular among the masses. Hindi cinema, in the later phase, divorced itself from socially relevant cinema and emerged as a pillar of the entertainment industry, by often serving the base emotions and patriarchal values of filmgoers.

As the article, Dalit Representation in Bollywood, and other pieces by critics highlight, the long history of Hindi cinema mostly revolves around the representation of the upper caste identities, brahmanical cultural rituals and Hindu aesthetics as the natural assets of the protagonist. It cleverly avoids reflecting on the issues of caste-based violence, social discrimination and emerging Dalit aspirations. Instead, in most cases, it imposes a structured narrative meant to address the emotive and psychological concerns of the Hindu social elites. Hindi films are often written, directed and produced by the social elites that overtly celebrate populist and non-artistic banal cinema. Even film critics, historians and scholars have studied cinema as popular art that is disconnected from rugged conflicting social realities. Bollywood, in the most visible way, is devoid of creative freedom, honesty and the passion to break conventional norms which can eventually produce a radical art form that is closer to the aspirations and the interests of the Dalit-Bahujan mass.

The task ahead

With the box-office success of films such as Sairat, Kabali, Masaan, Jai Bhim, Article 15, and, recently, Kantara, it was expected that cinema-makers would adopt Dalit-Bahujan narratives as a mainstream mode of film-making and engage the general audience. And, technicians, artists and producers who belonged to the Dalit-Bahujan communities would also contribute in bringing newer nuances in film narratives and democratise the hegemony of the social elites. However, for this to happen, a critical and sensitive Dalit-Bahujan audience will have to emerge as an intellectual audience, critically engaging with the the entertainment business. A discerning Dalit-Bahujan cinema audience will have to endorse a cinematic alternative that represents its social, cultural and political aspirations without diluting much of the entertainment quotient.

Harish S. Wankhede is Assistant Professor, Centre for Political Studies, School of Social Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi

[ad_2]