Amala Akkineni: Cinema is no longer about one person producing a masterpiece

[ad_1]

Amala Akkineni

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

It’s been eight years since Amala Akkineni took over as director of Annapurna College of Film and Media (ACFM), Hyderabad. She has been privy to changes in the entertainment sector with the scope to make shorts, feature films, web series and documentaries for theatrical release as well as streaming platforms. The film school is working towards getting its students to work with AI (artificial intelligence) and the virtual production stage. In an interview (video at www.thehindu.com) at her office, she takes stock of what these changes mean for aspiring filmmakers and what needs to change.

In 2015, Amala had observed that film education was a niche category as parents were hesitant to send their children to a film school, citing the unpredictable nature of work. That mindset has not changed drastically, she admits; medicine and engineering remain the preferred courses. However, she has observed more enthusiasm among second and third-generation film families to seek formal training. “They take to the curriculum like fish to water,” Amala says, mentioning how sons and daughters of cinematographers, sound engineers and other technical departments enrol for ACFM courses.

Amala cites a report (‘South India: Setting Benchmarks for the Nation in Media and Entertainment’ by Team MCube Insights) presented at the recent Confederation of Indian Industry Dakshin conference that reveals the South Indian entertainment and media sector has grown by 33% in 2022. “There is a need for trained film professionals now more than ever before since the corporates are stepping in. The corporate sector is particular about where you train, who are your mentors, whether you can work within a budget, and so on. All this comes with learning the basics.”

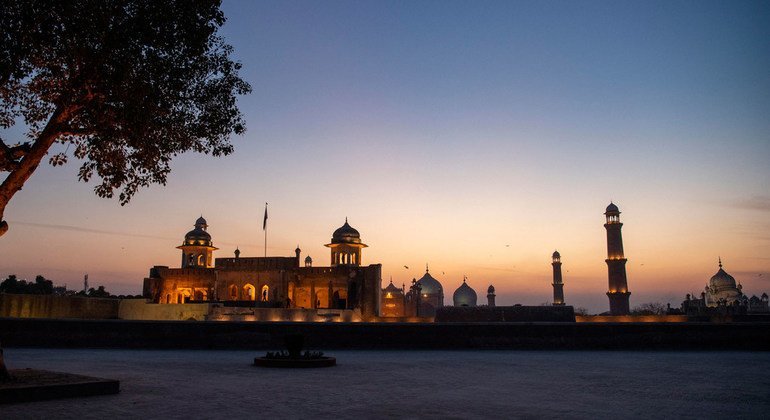

ANR Virtual Production Stage

Annapurna Studios recently announced the setting up of the ANR (Akkineni Nageswara Rao) Virtual Production Stage in association with Qube Cinema.

A virtual production stage combines physical and virtual productions and eliminates the green screen, which is now used by film units to shoot sequences that require visual effects to be added in the post production stage.

Imagine a filmmaker who wants to shoot a cyclone or a mountain range sequence. A 3D virtual projection of the required images (generated with the help of software) appears on the LED screen (curved, 20 feet tall and 60 feet wide) in the background while the actors are in the foreground. The resulting footage makes it appear as though the actors are in the environment.

Soon after the first lockdown, there was a surge in demand in the Telugu entertainment space for equipment and technicians to shoot feature films, web series and television shows, given the increased appetite of the audience for the content. Amala says it was a wake-up call. “The world had larger issues to deal with. Those in the entertainment industry were grateful for the opportunity to return to work. Everyone learnt to work with smaller crews, budgets and complete filming within a stipulated time. The OTT platforms that had begun to make inroads 10 years ago further established their markets. Filmmakers and technicians reinvented and re-organised themselves.” As for the film school, she mentions how at least 50 industry practitioners who were busy earlier were available to conduct online sessions. “Once the studios reopened, the students could apply theory into practice.”

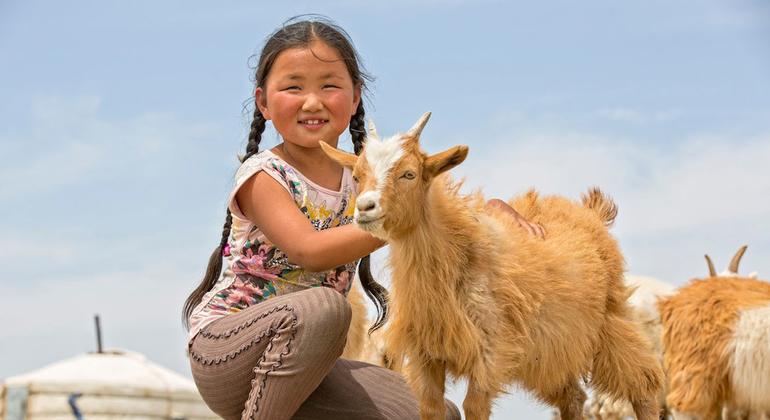

Shree Karthick and Amala Akkineni on the sets of ‘Kanam’/’Oke Oka Jeevitham’

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

While technical departments such as cinematography, sound design, visual effects, animation and editing are considered areas that require formal training, some aspirants feel that screenwriting and direction can be learnt intuitively, on the job. Drawing from her experience of having worked with generations of writers in different languages, Amala says, “It is the writer’s mind that produces the story. Good training imparts not just the process but also mentors young minds to write with depth rather than recreate ideas that they have observed in other movies. It is no longer about one writer or director producing a masterpiece; writers’ groups have taken over where each writer analyses a story from different angles. Representation is also brought in where necessary. If a character is that of a mature woman, a woman of that age group is consulted to help the writing be more authentic.”

She adds that students enter an institute at the age of 17 or 18 when they are still too young to be able to write or direct with maturity. She recalls a few filmmakers confiding in her how they felt lost on a film set, unfamiliar with the terms and way of work. After a formal course, they returned to the sets more confident.

A glimpse of the possibilities using ANR Virtual Production Stage

| Photo Credit:

Annapurna Studios

She explains that each year, the curriculum goes through changes with the inputs of the in-house academic council and the JNAFAU (Jawaharlal Nehru Architecture and Fine Arts University)’s advisory board. For instance, the board and the faculty observed that students who have grown up in an urban atmosphere have less exposure to rural culture and issues. Students had become familiar with filming in controlled environments but were less prepared for outdoor filming that comes with several challenges. Hence there has been more emphasis on filming in real-life outdoor situations and rural pockets.

Before she took up the responsibility at the film school, Amala had more or less stepped back from acting after director Sekhar Kammula’s Life is Beautiful (2012), barring a fleeting cameo in Manam (2014). Her later projects — Karwaan (Hindi), Kanam/Oke Oka Jeevitham (Tamil-Telugu bilingual), High Priestess (Telugu web series) and C/O Saira Banu (Malayalam) — gave her a ringside view of how the younger filmmakers worked. About her last film Kanam/Oke Oka Jeevitham, she says, “Shree Karthick was an ad filmmaker who was making his first film and the story (of the lead actor stepping into a time machine to revisit his mother) touched me. I was curious how a first-time director will pull this off. He was precise and meticulous in his preparation. On the sets, he would play specific ragas to get us into the mood of the scene that was to be filmed.”

Amala Akkineni

| Photo Credit:

Thulasi Kakkat

Similarly, theatre personality Akarsh Khurana was stepping into a new zone with the film Karwaan, and Pushpa Ignatius was taking on a web series for the first time. Amala says she uses these occasional acting assignments to observe new-gen filmmakers and impart those learnings at the film school. “All these films were small budget ventures. When a film graduate completes studies, he or she is more likely to work with smaller budgets and has to be quick and efficient, with bound scripts. There is no time to second guess on a set. The filmmaker and technicians need to be efficient. I was observing all this in front of me.”

Reflecting on her acting career, since the time she debuted in 1986 with the Tamil film Mythili Ennai Kadhali, as an untrained actor, she says Bharatanatyam inculcated in her the discipline to show up and work on cue every single day. “Dance expressions tend to be exaggerated as opposed to acting for cinema. My directors, including my first director T. Rajender, told me that they would teach me. And they did.” In the first few films, all she could hear was the whirring sound of the camera and other equipment, the bright lights and a motley crew staring at her. This was starkly different from being on stage and performing in front of a bigger audience. “My dance training taught me to take up a task, break it into small steps and complete them one by one. By the time I worked in Pushpak, I had gotten over my anxiety and fear of the camera.”

[ad_2]