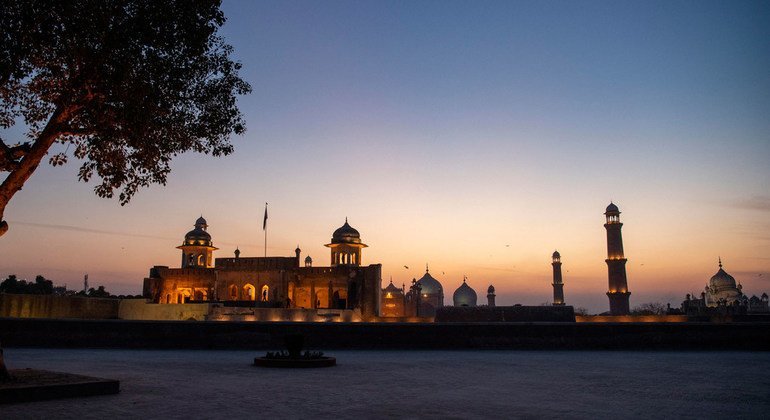

The human face of climate change

[ad_1]

Director Nila Madhab Panda

| Photo Credit: SPECIAL ARRANGEMENT

As the marauding flash floods in North India bring the issue of climate change into focus, National Award-winning filmmaker Nila Madhab Panda feels both vindicated and sad.

Having grown up in a modest household in an Odisha village, Nila, who has just finished his memoir and an OTT series that he describes as India’s first cli-fi (climate fiction), has seen the impact of climate change from close quarters and it reflects in his trilogy of films, Kaun Kitney Paani Main, Kadvi Hawa, and Kalira Atita, that addresses the raging issue.

“You don’t feel the problem when you are living it; when you look back you realise how and why it was. In my experience, it is always the poor, who have no role in polluting the environment, that are the worst affected by climate change. In Kalira Atita, based on a real story, the village that got submerged due to rising sea level had no electricity and hardly anybody had a motorcycle. The villagers hardly left a carbon footprint but their lives were ravaged.” To those who say climate change is not real, Nila asks why then Indonesia is shifting its capital from Jakarta.

Director Nila Madhab Panda

| Photo Credit:

SPECIAL ARRANGEMENT

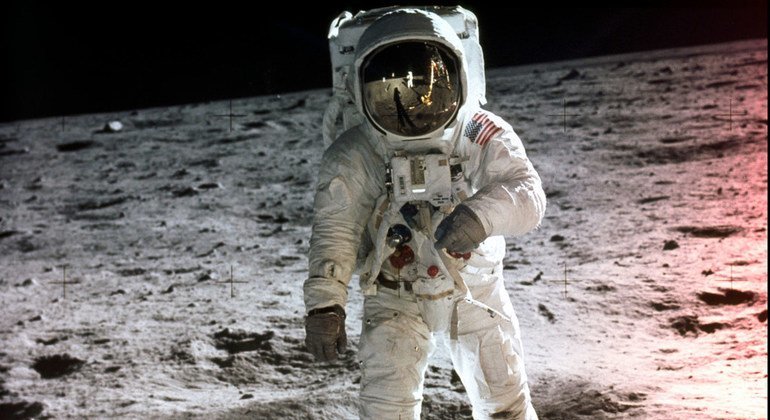

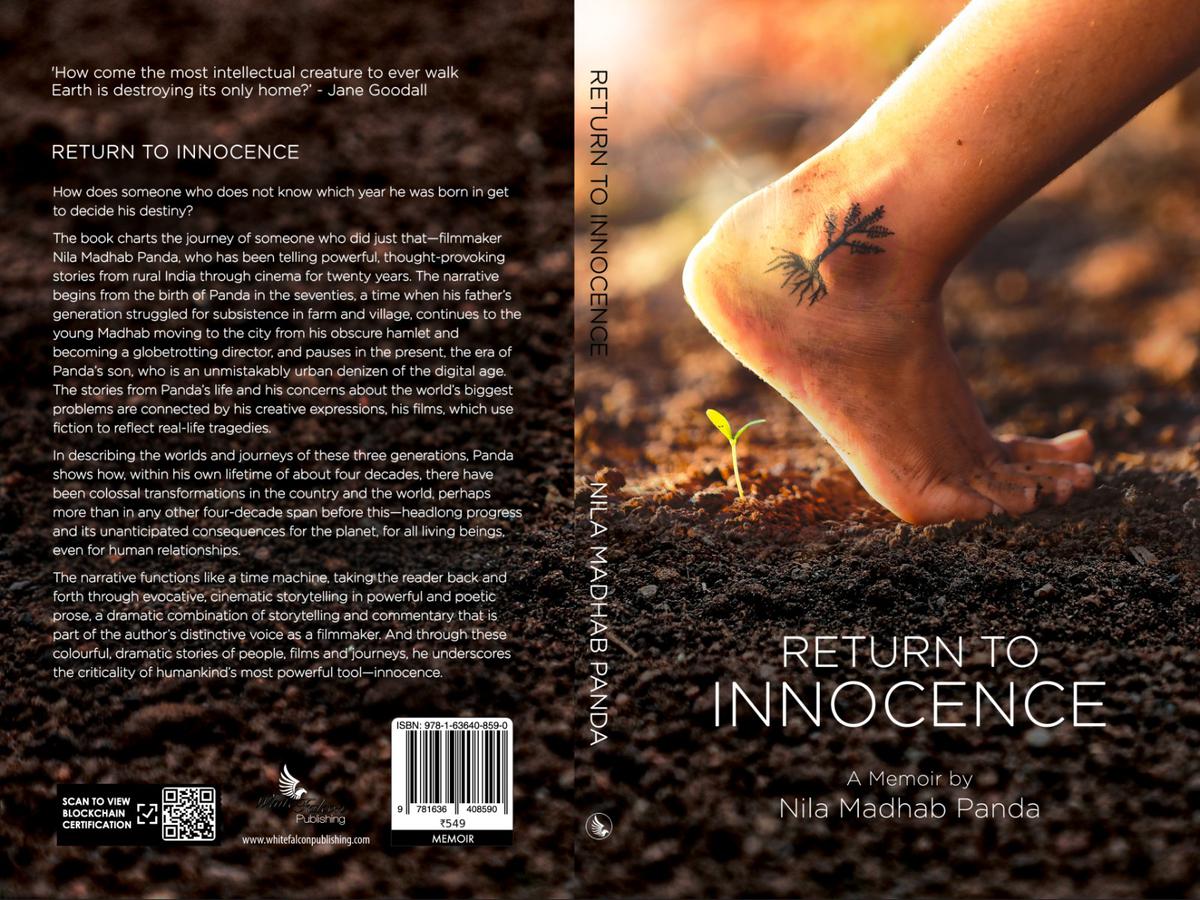

In Return to Innocence (White Falcon), Nila, who emerged on the scene with the much-feted I Am Kalam, argues the pandemic has been a slap in the face for humanity and yet we seem to have forgotten its lesson within a year and have returned to exploit Nature.

“We have a mythology that has survived millennia, we have historical accounts from thousands of years ago and yet we forget what happened just the day before. We are encouraged to live only in the present, only in indulgence and consumption, in a state of cultural and ecological amnesia. So, I want to tell people what happened yesterday, keep it for your and my tomorrow and for the next generation.” The memoir will be released by Nobel laureate Kailash Satyarthi with whom Nila has worked extensively and was in fact one of the inspirations behind I Am Kalam.

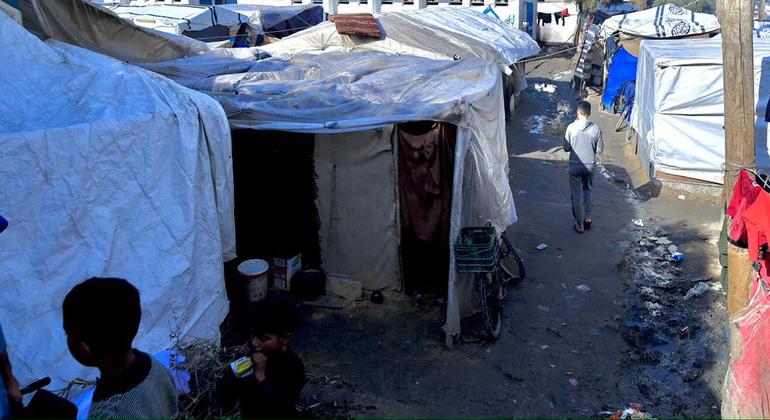

Hailing from undivided Bolangir, which along with Kalahandi and Koraput was one of most backward regions of the country, Nila says when he shifted to Delhi in the 1990s people would refer to Odisha as a “place where parents sell their children for food”. Today, he says, the State has made giant strides in financial and ecological sustainability because of political and social will. “Affected by both drought and cyclones, Odisha has now emerged as a shining example in disaster management with its excellent methods to tackle different natural calamities and their economic impact.”

”

Having started as a documentary filmmaker, the Padma Shri awardee feels sad when his work is reduced to that of a social activist. “I am a storyteller who looks for emotional tides amid ecological and man-made disasters. Unlike Hollywood films like Avatar that had an impact on raising the voice for the rights of the tribals on their land and natural resources, we have not been able to create a similar impactful work,” he says. But Hollywood’s superhero tales about saving the world and the growing role of artificial intelligence in the creative domain do not excite him, he adds.

Director Nila Madhab Panda’s book

| Photo Credit:

SPECIAL ARRANGEMENT

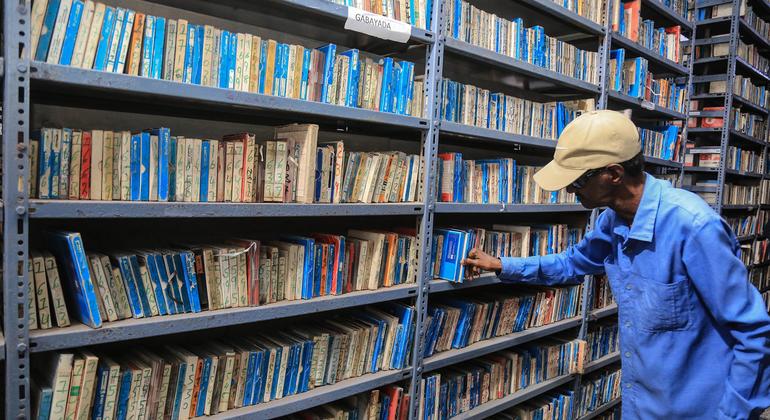

In The Jengaburu Curse, Nila addresses global concerns about mining and human greed with a story set in Odisha. Jengaburu means red hill in the tribal language. “The series follows a London-based financial analyst whose professor father mysteriously goes missing. Her search brings her to a small town in Odisha where she finds an unlikely connection between the indigenous Bonda tribe and the mining State.”

Starring Sudev Nair, Faria Abdullah, Nasser and Makarand Deshpande, the seven-part series will release later this year. “We had seen the impact of nuclear bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki but still we allowed Chernobyl to happen. It is a fictional story but draws from geopolitics that has a massive ecological impact.”

Real life: Director Nila Madhab Panda of Kadvi Hawa was inspired by the smog in Delhi to make his film.

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

Director Nila Madhab Panda

| Photo Credit:

SPECIAL ARRANGEMENT

[ad_2]